The coronavirus crisis has mercilessly exposed the dependence of the USA, the EU and Germany on Asian chip manufacturers. While demand for semiconductors exploded at the time, production lines in Germany came to a standstill – especially in the automotive industry.

Now chip production is to be brought back to Europe. Based on the EU Chip Act, the European share of semiconductor production is to increase to 20% by 2030. In June 2023, the EU approved funding for around 100 European projects, 31 of which are in Germany. But how sensible is this approach if the complex and labor-intensive testing, assembly and packaging of chips continues to take place almost exclusively in low-wage Asian countries?

“Without a comprehensive strategy that includes holistic production in our region, the goal remains half-hearted,” says Tobias Wölk, Product Manager Automation Technology & Active Components at reichelt elektronik. He is certain: “Europe can only achieve true sovereignty in semiconductor production through a fully Europeanized value chain – from front-end to back-end production. We not only need more manufacturing factories, but also a regional settlement of the processing industries. Otherwise, we will continue to be vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions and our dependence on Asia will remain. A European semiconductor market can only be truly independent if all production steps are anchored in this country.”

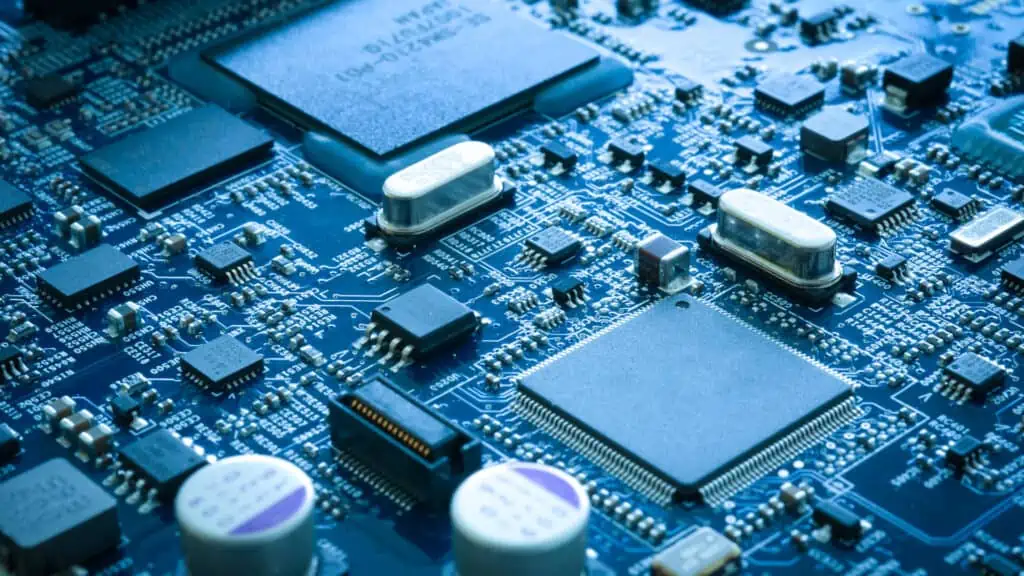

Semiconductor production – a globalized process

Bringing semiconductor production “back” to Europe is easier said than done. Today, it is a highly globalized process, with even industry-leading chip design companies outsourcing the production of their chips to external companies. For example, TSMC in Taiwan, the leading provider of contract manufacturing for semiconductors, produces chips for companies such as Apple, Intel and Nvidia. The various production phases themselves are also distributed across different regions of the world. Production takes place in two main phases: In front-end production, so-called wafers – thin slices of silicon – are provided with circuits and processed in such a way that chips are ultimately created. Once they have been fully processed, back-end production begins, which involves testing, assembling and packaging (TAP for short) the chips.

Many large semiconductor manufacturers have opted to outsource the less differentiated and more labor-intensive back-end manufacturing to specialized service providers in the Asian market in order to save costs. These external service providers are known as Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test Vendors (OSATs) and carry out this work on behalf of the major semiconductor companies. Nine of the world’s ten largest OSAT providers are located in the Asia-Pacific region (six in Taiwan, three in China).

Nothing works without chips: Europe’s response to its dependence on China and the USA

This complex manufacturing process makes global semiconductor supply chains particularly fragile. Geopolitical tensions, particularly in Taiwan, natural disasters or global crises such as the COVID pandemic can cut off a large proportion of European companies from semiconductor supplies. After all, nine out of ten industrial companies in Europe rely on semiconductors, and 80% consider them indispensable. This hardware technology is also essential for European digitalization efforts and the expansion of cloud, data centers and AI capacities.

The EU’s plan to strengthen European semiconductor production may therefore seem obvious. In mid-2023, the EU passed the so-called Chips Act – the package of measures worth 43 billion euros is intended to attract public and private investment, promote research and innovation and prepare Europe for future supply crises. The EU representatives have set themselves a lofty goal: to increase Europe’s share of the global semiconductor market from its current level of around 10 percent to 20 percent. No easy undertaking, especially as the USA already presented its CHIPS and Science Act in the summer of 2022 and provided 52.7 billion US dollars in funding.

Investment alone is not enough

The EU’s ambitious plan cannot simply be implemented in the reality of semiconductor production. Simply relocating front-end production will not solve Europe’s semiconductor dependency: OSAT capacities must be increased to the same extent as front-end production. Otherwise, the localization of semiconductor production in Europe will remain incomplete and ineffective, as the chips will still have to be sent abroad to be made ready for use.

The global production distribution of the different semiconductor structure widths makes purely European production even more difficult. The smaller the structure widths, the more powerful and efficient the semiconductors and therefore also the end devices. In December 2020, around 49% of European capacity was accounted for by structure widths of ≥ 0.18 micrometers. These semiconductors belong to an older generation and are used in almost all electrical devices today. However, this also means that if Europe wants to cover its own demand from local production, manufacturing must be multiplied.

There is also a lack of suitable workers to achieve the ambitious targets. According to calculations by PwC Strategy, there could be a shortage of around 350,000 employees by 2030 in order to achieve the EU’s ambitious 20% target. There is already a shortage of around 62,000 skilled workers in the semiconductor industry in Germany, particularly in the fields of electrical engineering, mechatronics and software development.

Another significant bottleneck is the dependence on Chinese silicon production. Silicon, the most important raw material for microchips, is largely produced in China – in 2023 alone, the country produced around 6.6 million tons of silicon, around ten times as much as the second-largest producing country, Russia. Experts already see that this availability at lower prices represents a competitive advantage for China that should not be underestimated in the production of solar cells. This dependency also makes Europe vulnerable to geopolitical tensions and supply disruptions. Europe must therefore not only build up production capacities and skilled workers, but also ensure a reliable and independent supply of raw materials.

The EU is still a long way from autonomous semiconductor production

The EU’s goal of achieving a 20% global market share in semiconductor production by 2030 is undoubtedly ambitious. However, there are currently neither sufficient funds nor enough skilled workers available to achieve this goal. In order to meet the current challenges, component production must instead be considered holistically. Europe should diversify its semiconductor supply chains and spread them across several regions in order to avoid dependencies. Close cooperation between industry, government and educational institutions is crucial to train and attract the skilled workers needed. At the same time, bureaucratic hurdles must be removed and investment in research, development and infrastructure massively increased. Only through a coordinated and integrative approach can Europe realize its vision of a strong and independent semiconductor industry and compete successfully in the global marketplace.

(lb/reichelt elektronik)